Systemic Lupus Erythematosus also called SLE or Lupus

Common Symptoms of Lupus

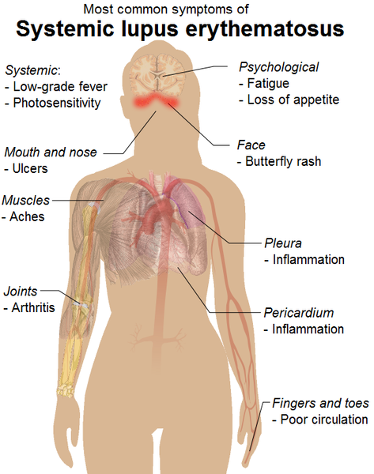

- Painful or swollen joints and muscle pain

- Unexplained fever

- Red rashes, most commonly on the face

- Chest pain upon deep breathing

- Unusual loss of hair

- Pale or purple fingers or toes from cold or stress (Raynaud's phenomenon)

- Sensitivity to the sun

- Swelling (edema) in legs or around eyes

- Mouth ulcers

- Swollen glands

- Extreme fatigue.

Defining Lupus

Lupus is one of many disorders of the immune system known as autoimmune diseases. In autoimmune diseases, the immune system turns against parts of the body it is designed to protect. This leads to inflammation and damage to various body tissues. Lupus can affect many parts of the body, including the joints, skin, kidneys, heart, lungs, blood vessels, and brain. Although people with the disease may have many different symptoms, some of the most common ones include extreme fatigue, painful or swollen joints (arthritis), unexplained fever, skin rashes, and kidney problems.

At present, there is no cure for lupus. However, lupus can be effectively treated with drugs, and most people with the disease can lead active, healthy lives. Lupus is characterized by periods of illness, called flares, and periods of wellness, or remission. Understanding how to prevent flares and how to treat them when they do occur helps people with lupus maintain better health. Intense research is underway, and scientists funded by the NIH are continuing to make great strides in understanding the disease, which may ultimately lead to a cure.

Two of the major questions researchers are studying are who gets lupus and why. We know that many more women than men have lupus. Lupus is two to three times more common in African American women than in Caucasian women and is also more common in women of Hispanic, Asian, and Native American descent. African American and Hispanic women are also more likely to have active disease and serious organ system involvement. In addition, lupus can run in families, but the risk that a child or a brother or sister of a patient will also have lupus is still quite low. It is difficult to estimate how many people in the United States have the disease, because its symptoms vary widely and its onset is often hard to pinpoint.

There are several kinds of lupus:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the form of the disease that most people are referring to when they say “lupus.” The word “systemic” means the disease can affect many parts of the body. The symptoms of SLE may be mild or serious. Although SLE usually first affects people between the ages of 15 and 45 years, it can occur in childhood or later in life as well. This booklet focuses on SLE.

- Discoid lupus erythematosus is a chronic skin disorder in which a red, raised rash appears on the face, scalp, or elsewhere. The raised areas may become thick and scaly and may cause scarring. The rash may last for days or years and may recur. A small percentage of people with discoid lupus have or develop SLE later.

- Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus refers to skin lesions that appear on parts of the body exposed to sun. The lesions do not cause scarring.

- Drug-induced lupus is a form of lupus caused by medications. Many different drugs can cause drug-induced lupus. They include some antiseizure medications, high blood pressure medications, antibiotics and antifungals, thyroid medications, and oral contraceptive pills. Symptoms are similar to those of SLE (arthritis, rash, fever, and chest pain), and they typically go away completely when the drug is stopped. The kidneys and brain are rarely involved.

- Neonatal lupus is a rare disease that can occur in newborn babies of women with SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, or no disease at all. Scientists suspect that neonatal lupus is caused in part by autoantibodies in the mother’s blood called anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB). Autoantibodies (“auto” means self) are blood proteins that act against the body’s own parts. At birth, the babies have a skin rash, liver problems, and low blood counts. These symptoms gradually go away over several months. In rare instances, babies with neonatal lupus may have congenital heart block, a serious heart problem in which the formation of fibrous tissue in the baby’s heart interferes with the electrical impulses that affect heart rhythm. Neonatal lupus is rare, and most infants of mothers with SLE are entirely healthy. All women who are pregnant and known to have anti-Ro (SSA) or anti-La (SSB) antibodies should be monitored by echocardiograms (a test that monitors the heart and surrounding blood vessels) during the 16th and 30th weeks of pregnancy. It is important for women with SLE or other related autoimmune disorders to be under a doctor’s care during pregnancy. Doctors can now identify mothers at highest risk for complications, allowing for prompt treatment of the infant at or before birth. SLE can also flare during pregnancy, and prompt treatment can keep the mother healthier longer.

Understanding What Causes Lupus

In studies of identical twins—who are born with the exact same genes—when one twin has lupus, the other twin has a 24-percent chance of developing it. This and other research suggests that genetics plays an important role, but it also shows that genes alone do not determine who gets lupus, and that other factors play a role. Some of the factors scientists are studying include sunlight, stress, hormones, cigarette smoke, certain drugs, and infectious agents such as viruses. Recent research has confirmed that one virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which causes mononucleosis, is a cause of lupus in genetically susceptible people.

Scientists believe there is no single gene that predisposes people to lupus. Rather, studies suggest that a number of different genes may be involved in determining a person’s likelihood of developing the disease, which tissues and organs are affected, and the severity of disease. Researchers have begun to make headway in identifying some of those genes, which could eventually lead to better ways to treat and perhaps even prevent lupus.

In lupus, the body’s immune system does not work as it should. A healthy immune system produces proteins called antibodies and specific cells called lymphocytes that help fight and destroy viruses, bacteria, and other foreign substances that invade the body. In lupus, the immune system produces antibodies against the body’s healthy cells and tissues. These antibodies, called autoantibodies, contribute to the inflammation of various parts of the body and can cause damage to organs and tissues. The most common type of autoantibody that develops in people with lupus is called an antinuclear antibody (ANA) because it reacts with parts of the cell’s nucleus (command center). Doctors and scientists do not yet understand all of the factors that cause inflammation and tissue damage in lupus, and researchers are actively exploring them.

Acute cutaneous lupus has a malar rash–flattened areas of red skin on the face that look like sunburn.

Symptoms of Lupus

Each person with lupus has slightly different symptoms that can range from mild to severe and may come and go over time. However, some of the most common symptoms of lupus include painful or swollen joints (arthritis), unexplained fever, and extreme fatigue. A characteristic red skin rash—the so-called butterfly or malar rash—may appear across the nose and cheeks. Rashes may also occur on the face and ears, upper arms, shoulders, chest, and hands and other areas exposed to the sun. Because many people with lupus are sensitive to sunlight (called photosensitivity), skin rashes often first develop or worsen after sun exposure.

Other symptoms of lupus include chest pain, hair loss, anemia (a decrease in red blood cells), mouth ulcers, and pale or purple fingers and toes from cold and stress. Some people also experience headaches, dizziness, depression, confusion, or seizures. New symptoms may continue to appear years after the initial diagnosis, and different symptoms can occur at different times. In some people with lupus, only one system of the body, such as the skin or joints, is affected. Other people experience symptoms in many parts of their body. Just how seriously a body system is affected varies from person to person. The following systems in the body also can be affected by lupus.

- Kidneys: Inflammation of the kidneys (nephritis) can impair their ability to get rid of waste products and other toxins from the body effectively. There is usually no pain associated with kidney involvement, although some patients may notice dark urine and swelling around their eyes, legs, ankles, or fingers. Most often, the only indication of kidney disease is an abnormal urine or blood test. Because the kidneys are so important to overall health, lupus affecting the kidneys generally requires intensive drug treatment to prevent permanent damage.

- Lungs: Some people with lupus develop pleuritis, an inflammation of the lining of the chest cavity that causes chest pain, particularly with breathing. Patients with lupus also may get pneumonia.

- Central nervous system: In some patients, lupus affects the brain or central nervous system. This can cause headaches, dizziness, depression, memory disturbances, vision problems, seizures, stroke, or changes in behavior.

- Blood vessels: Blood vessels may become inflamed (vasculitis), affecting the way blood circulates through the body. The inflammation may be mild and may not require treatment or may be severe and require immediate attention. People with lupus are also at increased risk for atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

- Blood: People with lupus may develop anemia, leukopenia (a decreased number of white blood cells), or thrombocytopenia (a decrease in the number of platelets in the blood, which assist in clotting). People with lupus who have a type of autoantibody called antiphospholipid antibodies have an increased risk of blood clots.

- Heart: In some people with lupus, inflammation can occur in the heart itself (myocarditis and endocarditis) or the membrane that surrounds it (pericarditis), causing chest pains or other symptoms. Endocarditis can damage the heart valves, causing the valve surface to thicken and develop growths, which can cause heart murmurs. However, this usually doesn’t affect the valves’ function.

In lupus, the immune system can damage healthy red blood cells, causing a condition called hemolytic anemia. This can create jaundice of the eye - a yellowish color to the eyes.

Diagnosing Lupus

Diagnosing lupus can be difficult. It may take months or even years for doctors to piece together the symptoms to diagnose this complex disease accurately. Making a correct diagnosis of lupus requires knowledge and awareness on the part of the doctor and good communication on the part of the patient. Giving the doctor a complete, accurate medical history (for example, what health problems you have had and for how long) is critical to the process of diagnosis. This information, along with a physical examination and the results of laboratory tests, helps the doctor consider other diseases that may mimic lupus, or determine if you truly have the disease. Reaching a diagnosis may take time as new symptoms appear.

No single test can determine whether a person has lupus, but several laboratory tests may help the doctor to confirm a diagnosis of lupus or rule out other causes for a person’s symptoms. The most useful tests identify certain autoantibodies often present in the blood of people with lupus. For example, the antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is commonly used to look for autoantibodies that react against components of the nucleus, or “command center,” of the body’s cells. Most people with lupus test positive for ANA; however, there are a number of other causes of a positive ANA besides lupus, including infections and other autoimmune diseases, and occasionally it is found in healthy people. The ANA test simply provides another clue for the doctor to consider in making a diagnosis. In addition, there are blood tests for individual types of autoantibodies that are more specific to people with lupus, although not all people with lupus test positive for these and not all people with these antibodies have lupus. These antibodies include anti-DNA, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB). The doctor may use these antibody tests to help make a diagnosis of lupus.

Some tests are used less frequently but may be helpful if the cause of a person’s symptoms remains unclear. The doctor may order a biopsy of the skin or kidneys if those body systems are affected. Some doctors may order a test for anticardiolipin (or antiphospholipid) antibody. The presence of this antibody may indicate increased risk for blood clotting and increased risk for miscarriage in pregnant women with lupus. Again, all these tests merely serve as tools to give the doctor clues and information in making a diagnosis. The doctor will look at the entire picture—medical history, symptoms, and test results—to determine if a person has lupus.

Diagnostic Tools for Lupus

- Medical history

- Complete physical examination

- Laboratory tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Urinalysis

- Blood chemistries

- Complement levels

- Antinuclear antibody test (ANA)

- Other autoantibody tests (anti-DNA, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-Ro [SSA], anti‑La [SSB])

- Anticardiolipin antibody test

- Skin biopsy

- Kidney biopsy.

Other laboratory tests are used to monitor the progress of the disease once it has been diagnosed. A complete blood count, urinalysis, blood chemistries, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate test (a test to measure inflammation) can provide valuable information. Another common test measures the blood level of a group of substances called complement, which help antibodies fight invaders. A low level of complement could mean the substance is being used up because of an immune response in the body, such as that which occurs during a flare of lupus.

X rays and other imaging tests can help doctors see the organs affected by SLE.

Treating Lupus

Diagnosing and treating lupus often require a team effort between the patient and several types of health care professionals. A person with lupus can go to his or her family doctor or internist, or can visit a rheumatologist. A rheumatologist is a doctor who specializes in rheumatic diseases (arthritis and other inflammatory disorders, often involving the immune system). Clinical immunologists (doctors specializing in immune system disorders) may also treat people with lupus. As treatment progresses, other professionals often help. These may include nurses, psychologists, social workers, nephrologists (doctors who treat kidney disease), cardiologists (doctors specializing in the heart and blood vessels), hematologists (doctors specializing in blood disorders), endocrinologists (doctors specializing in problems related to the glands and hormones), dermatologists (doctors who treat skin disease), and neurologists (doctors specializing in disorders of the nervous system).

The range and effectiveness of treatments for lupus have increased dramatically in recent decades, giving doctors more choices in how to manage the disease. It is important for the patient to work closely with the doctor and take an active role in managing the disease. Once lupus has been diagnosed, the doctor will develop a treatment plan based on the patient’s age, sex, health, symptoms, and lifestyle. Treatment plans are tailored to the individual’s needs and may change over time. In developing a treatment plan, the doctor has several goals: to prevent flares, to treat them when they do occur, and to minimize organ damage and complications. The doctor and patient should reevaluate the plan regularly to ensure it is as effective as possible.

NSAIDs: For people with joint or chest pain or fever, drugs that decrease inflammation, called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are often used. Although some NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, are available over the counter, a doctor’s prescription is necessary for others. NSAIDs may be used alone or in combination with other types of drugs to control pain, swelling, and fever. Even though some NSAIDs may be purchased without a prescription, it is important that they be taken under a doctor’s direction. Common side effects of NSAIDs can include stomach upset, heartburn, diarrhea, and fluid retention. Some people with lupus also develop liver, kidney, or even neurological complications, making it especially important to stay in close contact with the doctor while taking these medications.

Antimalarials: Antimalarials are another type of drug commonly used to treat lupus. These drugs were originally used to treat malaria, but doctors have found that they also are useful for lupus. A common antimalarial used to treat lupus is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil1). It may be used alone or in combination with other drugs and generally is used to treat fatigue, joint pain, skin rashes, and inflammation of the lungs. Clinical studies have found that continuous treatment with antimalarials may prevent flares from recurring. Side effects of antimalarials can include stomach upset and, extremely rarely, damage to the retina of the eye.

1Brand names included in this publication are provided as examples only, and their inclusion does not mean that these products are endorsed by the National Institutes of Health or any other Government agency. Also, if a particular brand name is not mentioned, this does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

Corticosteroids: The mainstay of lupus treatment involves the use of corticosteroid hormones, such as prednisone (Deltasone), hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone (Medrol), and dexamethasone (Decadron, Hexadrol). Corticosteroids are related to cortisol, which is a natural anti-inflammatory hormone. They work by rapidly suppressing inflammation. Corticosteroids can be given by mouth, in creams applied to the skin, by injection, or by intravenous (IV) infusion (dripping the drug into the vein through a small tube). Because they are potent drugs, the doctor will seek the lowest dose with the greatest benefit. Short-term side effects of corticosteroids include swelling, increased appetite, and weight gain. These side effects generally stop when the drug is stopped. It is dangerous to stop taking corticosteroids suddenly, so it is very important that the doctor and patient work together in changing the corticosteroid dose. Sometimes doctors give very large amounts of corticosteroid by IV infusion over a brief period of time (days) (“bolus” or “pulse” therapy). With this treatment, the typical side effects are less likely and slow withdrawal is unnecessary.

Long-term side effects of corticosteroids can include stretch marks on the skin, weakened or damaged bones (osteoporosis and osteonecrosis), high blood pressure, damage to the arteries, high blood sugar (diabetes), infections, and cataracts. Typically, the higher the dose and the longer they are taken, the greater the risk and severity of side effects. Researchers are working to develop ways to limit or offset the use of corticosteroids. For example, corticosteroids may be used in combination with other, less potent drugs, or the doctor may try to slowly decrease the dose once the disease is under control. People with lupus who are using corticosteroids should talk to their doctors about taking supplemental calcium and vitamin D or other drugs to reduce the risk of osteoporosis (weakened, fragile bones).

Immunosuppressives: For some patients whose kidneys or central nervous systems are affected by lupus, a type of drug called an immunosuppressive may be used. Immunosuppressives, such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) and mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), restrain the overactive immune system by blocking the production of immune cells. These drugs may be given by mouth or by IV infusion. Side effects may include nausea, vomiting, hair loss, bladder problems, decreased fertility, and increased risk of cancer and infection. The risk for side effects increases with the length of treatment. As with other treatments for lupus, there is a risk of relapse after the immunosuppressives have been stopped.

BLyS-specific inhibitors: Belimumab (Benlysta), a B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) protein inhibitor, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2011 for patients with lupus who are receiving other standard therapies, including those listed above. Given by IV infusion, it may reduce the number of abnormal B cells thought to be a problem in lupus. The most common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and fever. Patients may also experience reactions at the infusion site, for which antihistamines can be given in advance. Less commonly, serious infections may result.

In studies conducted so far, African American patients and patients of African heritage did not appear to respond to belimumab. An additional study of this patient population will be conducted to further evaluate belimumab in this subgroup of lupus patients. However, this difference in response to a treatment may be another indicator of the various ways that the disease affects different patients.

Other therapies: In some patients, methotrexate (Folex, Mexate, Rheumatrex), a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, may be used to help control the disease. Other treatments may include hormonal therapies such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and intravenous immunoglobulin (proteins derived from human blood), which may be useful for controlling lupus when other treatments haven’t worked.

Working closely with the doctor helps ensure that treatments for lupus are as successful as possible. Because some treatments may cause harmful side effects, it is important to report any new symptoms to the doctor promptly. It is also important not to stop or change treatments without talking to the doctor first. In addition to medications for lupus itself, in many cases it may be necessary to take additional medications to treat problems related to lupus such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure, or infection.

Alternative and complementary therapies: Because of the nature and cost of the medications used to treat lupus and the potential for serious side effects, many patients seek other ways of treating the disease. Some alternative approaches people have tried include special diets, nutritional supplements, fish oils, ointments and creams, chiropractic treatment, and homeopathy. Although these methods may not be harmful in and of themselves and may be associated with symptomatic or psychosocial benefit, no research to date shows that they affect the disease process or prevent organ damage. Some alternative or complementary approaches may help the patient cope or reduce some of the stress associated with living with a chronic illness. If the doctor feels the approach has value and will not be harmful, it can be incorporated into the patient’s treatment plan. However, it is important not to neglect regular health care or treatment of serious symptoms. An open dialogue between the patient and doctor about the relative values of complementary and alternative therapies allows the patient to make an informed choice about treatment options.

Lupus and Quality of Life

A diagnosis of lupus can have a significant impact on quality of life, including the ability to work. Recent research on work loss associated with lupus, funded in part by the NIAMS, estimated that almost three-quarters of the study’s 982 participants would stop working before the usual age of retirement, and that half of those who had jobs when they were diagnosed (during their mid-thirties, on average) would no longer be working by the age of 50. The researchers determined that demographics and work characteristics (the physical and psychological demands of jobs and the degree of control over assignments and work environment) had the most impact on work loss.

Despite the symptoms of lupus and the potential side effects of treatment, people with lupus can maintain a high quality of life overall. One key to managing lupus is to understand the disease and its impact. Learning to recognize the warning signs of a flare can help the patient take steps to ward it off or reduce its intensity. Many people with lupus experience increased fatigue, pain, a rash, fever, abdominal discomfort, headache, or dizziness just before a flare. Developing strategies to prevent flares can also be helpful, such as learning to recognize your warning signals and maintaining good communication with your doctor.

It is also important for people with lupus to receive regular health care, instead of seeking help only when symptoms worsen. Results from a medical exam and laboratory work on a regular basis allows the doctor to note any changes and to identify and treat flares early. The treatment plan, which is tailored to the individual’s specific needs and circumstances, can be adjusted accordingly. If new symptoms are identified early, treatments may be more effective. Other concerns also can be addressed at regular checkups. The doctor can provide guidance about such issues as the use of sunscreens, stress reduction, and the importance of structured exercise and rest, as well as birth control and family planning. Because people with lupus can be more susceptible to infections, the doctor may recommend yearly influenza vaccinations or pneumococcal vaccinations for some patients.

Women with lupus should receive regular preventive health care, such as gynecological and breast examinations. Men with lupus should have the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Both men and women need to have their blood pressure and cholesterol checked on a regular basis. If a person is taking corticosteroids or antimalarial medications, an eye exam should be done at least yearly to screen for and treat eye problems.

People with lupus should also be aware of their increased risk of premature cardiovascular disease. This makes healthy lifestyle choices such as eating well, exercising regularly, and not smoking particularly important for people with lupus.

Warning Signs of a Flare

- Increased fatigue

- Pain

- Rash

- Fever

- Abdominal discomfort

- Headache

- Dizziness.

Preventing a Flare

- Learn to recognize your warning signals.

- Maintain good communication with your doctor.

Staying healthy requires extra effort and care for people with lupus, so it becomes especially important to develop strategies for maintaining wellness. Wellness involves close attention to the body, mind, and spirit. One of the primary goals of wellness for people with lupus is coping with the stress of having a chronic disorder. Effective stress management varies from person to person. Some approaches that may help include exercise, relaxation techniques such as meditation, and setting priorities for spending time and energy.

Developing and maintaining a good support system is also important. A support system may include family, friends, medical professionals, community organizations, and support groups. Participating in a support group can provide emotional help, boost self-esteem and morale, and help develop or improve coping skills. (For more information on support groups, see the “For More Information” section at the end of this booklet.)

Tips for Working With Your Doctor

- Seek a health care provider who is familiar with SLE and who will listen to and address your concerns.

- Provide complete, accurate medical information.

- Make a list of your questions and concerns in advance.

- Be honest and share your point of view with the health care provider.

- Ask for clarification or further explanation if you need it.

- Talk to other members of the health care team, such as nurses, therapists, or pharmacists.

- Do not hesitate to discuss sensitive subjects (for example, birth control, intimacy) with your doctor.

- Discuss any treatment changes with your doctor before making them.

Pregnancy and Contraception for Women With Lupus

Although pregnancy in women with lupus is considered high risk, most women with lupus carry their babies safely to the end of their pregnancy. Women with lupus in general have a higher rate of miscarriage and premature births compared with the general population. In addition, women who have antiphospholipid antibodies are at a greater risk of miscarriage in the second trimester because of their increased risk of blood clotting in the placenta. Lupus patients with a history of kidney disease have a higher risk of preeclampsia (hypertension with a buildup of excess watery fluid in cells or tissues of the body). Pregnancy counseling and planning before pregnancy are important. Ideally, a woman should have no signs or symptoms of lupus and be taking no medications for at least 6 months before she becomes pregnant.

Some women may experience a mild to moderate flare during or after their pregnancy; others do not. Pregnant women with lupus, especially those taking corticosteroids, also are more likely to develop high blood pressure, diabetes, hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), and kidney complications, so regular care and good nutrition during pregnancy are essential. It is also advisable to have access to a neonatal (newborn) intensive care unit at the time of delivery in case the baby requires special medical attention.

For women with lupus who do not wish to become pregnant or who are taking drugs that could be harmful to an unborn baby, reliable birth control is important. Previously, oral contraceptives (birth control pills) were not an option for women with lupus because doctors feared the hormones in the pill would cause a flare of the disease. However, a large NIH-supported study called Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment (SELENA) found that severe flares were no more common among women with lupus taking oral contraceptives than those taking a placebo (inactive pill). As a result of this study, published in 2005, doctors are increasingly prescribing oral contraceptives to women with inactive or stable disease.

Current Research

Lupus is the focus of intense research as scientists try to determine what causes the disease and how it can best be treated. Some of the questions they are working to answer include: Why are women more likely than men to have the disease? Why are there more cases of lupus in some racial and ethnic groups, and why are cases in these groups often more severe? What goes wrong in the immune system and why? How can we correct the way the immune system functions once something goes wrong? What treatment approaches will work best to lessen lupus symptoms? How do we cure lupus?

To help answer these questions, scientists are developing new and better ways to study the disease. They are doing laboratory studies that compare various aspects of the immune systems of people with lupus with those of other people both with and without lupus. They also use mice with disorders resembling lupus to better understand the abnormalities of the immune system that occur in lupus and to identify possible new therapies.

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health (NIH), has a major focus on lupus research in its on-campus program in Bethesda, Maryland. By evaluating patients with lupus and their relatives, researchers at the NIH are learning more about how lupus develops and changes over time.

The NIAMS also funds many lupus researchers across the United States. To help scientists gain new knowledge, the NIAMS sponsored the development of a Lupus Registry and Repository that gathers medical information, as well as blood and tissue samples from patients and their relatives. This gives researchers across the country access to information and materials they can use to help identify genes that determine susceptibility to the disease.

The NIAMS also helped establish a registry to collect information and blood samples from children affected by neonatal lupus and their mothers. Information from the registry forms the basis of family counseling and tracks important data such as recurrence rates in subsequent pregnancies. The hope is that the registry will facilitate improved methods of diagnosis, as well as prevention and treatment for this rare condition.

In 2003, the NIH established the Lupus Federal Working Group (LFWG), a collaboration among the NIH Institutes, other Federal agencies, voluntary and professional organizations, and industries with an interest in lupus. The Working Group is led by the NIAMS and includes representatives from all relevant U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) agencies and other Federal departments having an interest in lupus.

Here are some recent major advances in different areas of lupus research:

Genetics

Identifying genes that play a role in the development of lupus or lupus severity is an active area of research.

The NIAMS intramural and extramural investigators have established that a variant in a gene called STAT4, which is associated with lupus susceptibility, is more specifically associated with disease characterized by severe symptoms such as disorders of the kidney. This finding may allow doctors to determine which patients are at risk of more severe disease and may lead to the development of new treatment for patients at greatest risk of complications.

Scientists have also found a gene that may confer susceptibility to lupus. They have shown that having an alternative form of the gene Ly108 may impair the body’s ability to keep self-destructive B cells in check. This gene is part of a gene family (SLAM) that has been linked to lupus-like disease in mice.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers are another significant area of lupus research. Biomarkers are defined as molecules that reflect a specific biological or pathological process, consequence of a process, or a response to a therapeutic intervention. Simply put, they can let the doctor know what is happening in the body—or predict what is going to happen—based on something reliably measurable in tissues, cells, or fluids. NIAMS-supported researchers have identified anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies and complement C3a—both of which can be found in blood tests—as biomarkers for flares, meaning they can predict that a flare will occur. They also showed that moderate doses of prednisone can prevent flares in people having these biomarkers.

In separate research, NIAMS-supported investigators identified a list of proteins in the urine of people with renal disease caused by lupus. These biomarkers can be used to indicate the type and severity of renal disease in these patients, as well as the extent of damage to the kidney. Such biomarkers could form the basis of clinical tests to help doctors establish an effective treatment plan for these patients without putting them through repeated kidney biopsies. Further studies are needed to determine whether urine protein analysis could replace the use of biopsies to assess kidney damage in lupus.

The Disease Process

One recent NIAMS-supported study found that the disease process of lupus—including the development of certain autoantibodies and some symptoms of the disease—begin before the disease is diagnosed. Because lupus is different in different people and is characterized by autoimmunity in various systems of the body, the initial presentation can be unpredictable. Many symptoms wax and wane over time, often delaying diagnosis and the start of therapy.

Seeking to identify patterns among early clinical events in lupus, as well as to assess whether the presence of lupus-associated autoantibodies precedes clinical manifestations, investigators looked back at the charts of 130 lupus patients, analyzing 633 serum samples taken at different times and noting when the criteria for a lupus diagnosis were fulfilled. To be classified as having lupus, a person needs to meet at least 4 of 11 criteria. They found that in 80 percent of the patients, at least one clinical criterion for SLE appeared before SLE was diagnosed. Eighty-four percent developed antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). Discoid rashes and seizures were the earliest observed symptoms, with a mean onset of 1.74 years and 1.70 years prior to diagnosis, respectively. Oral ulcers tended to appear only after diagnosis, making this a less useful diagnostic tool. Among SLE patients with renal disease, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies appeared before or at the same time as American College of Rheumatology (ACR)-defined renal disorder in the majority of patients who had both the autoantibodies and the renal disorder.

Researchers are also making strides in understanding how the disease process affects different organs. One NIAMS investigator reported that a subset of antibodies to DNA can be found in the blood and the brain of lupus patients with cognitive problems. These anti-DNA antibodies bind to specific receptors (NMDA [N-methyl-d-aspartate] receptors) on nerve cells in the brain. In the culture dish, binding of these anti-DNA antibodies to nerve cells results in the death of the cells. In subsequent studies involving mice, the researchers found that these antibodies affect the nervous system only when the blood-brain barrier was broken, allowing the antibodies access to the brain. Where the blood-brain barrier was broken, antibodies bound to the neurons in a specific area of the brain that helps regulate emotion and memory. Tests for cell death in that area of the brain were positive. Behavioral tests on the mice also revealed impaired cognitive function and memory. Perhaps more important was the finding that the nerve cell binding and its damage could be prevented with a drug that inhibits the NMDA receptor. Researchers say the findings suggest that such drugs may eventually be a useful therapy for people with lupus.

Treatment

Understandably, identifying and developing better treatments for lupus—and ensuring that patients receive the best treatments—are among the primary goals of lupus research. A 2005 study of 17 adults with lupus that was clinically active despite treatment, found that just one injection of the cancer drug rituximab (Rituxan) eased symptoms for up to a year or more. Several participants were able to reduce or completely stop their regular lupus medications. Rituximab works by lowering the number of B cells—white blood cells that produce antibodies—in the body. It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a type of cancer called lymphoma, as well as for rheumatoid arthritis. Further research is needed to better understand its effectiveness and safety and to better determine its role in lupus treatment.

Other research is examining barriers that keep certain populations from complying with their prescribed medical treatment, which could contribute to worse disease outcomes, including disability and death in those populations. One NIAMS-supported study of economically disadvantaged and ethnically diverse people with rheumatoid arthritis or lupus identified fear of side effects, including long-term damage, as a major reason people failed to take prescribed medications for their disease. Other factors identified included belief that medicines are not working, problems with health system such as navigating Medicaid requirements and a lack of continuity with the same doctor, and medication cost.

More information on research is available from the following resources:

- ClinicalTrials.gov offers up-to-date information for locating federally and privately supported clinical trials for a wide range of diseases and conditions.

- NIH RePORTER is an electronic tool that allows users to search a repository of both intramural and extramural NIH-funded research projects from the past 25 years and access publications (since 1985) and patents resulting from NIH funding.

- PubMed is a free service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine that lets you search millions of journal citations and abstracts in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and preclinical sciences.

Hope for the Future

With research advances and a better understanding of lupus, the prognosis for people with lupus today is far brighter than it was in the past. It is possible to have lupus and remain active and involved with life, family, and work. As current research efforts unfold, there is continued hope for new treatments, improvements in quality of life, and, ultimately, a way to prevent or cure the disease. The research efforts of today may yield the answers of tomorrow, as scientists continue to unravel the mysteries of lupus.

For More Information

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)

Information Clearinghouse National Institutes of Health 1 AMS Circle Bethesda, MD 20892-3675 Phone: 301-495-4484 Toll Free: 877-22-NIAMS (877-226-4267) Email: NIAMSinfo@mail.nih.gov Website: http://www.niams.nih.gov

Other Resources

American College of Rheumatology

Website: http://www.rheumatology.org

Alliance for Lupus Research, Inc.

Website: http://www.lupusresearch.org

American Autoimmune-Related Diseases Association, Inc. (AARDA)

Website: http://www.aarda.org

Arthritis Foundation

Website: http://www.arthritis.org

Lupus Clinical Trials Consortium, Inc. (LCTC)

Website: http://www.lupusclinicaltrials.org

Lupus Foundation of America (LFA)

Website: http://www.lupus.org

Lupus Research Institute

Website: www.lupusresearchinstitute.org

Rheuminations, Inc.

Website: http://www.dxlupus.org

SLE Lupus Foundation

Website: http://www.lupusny.org

For additional contact information, visit the NIAMS website or call the NIAMS Information Clearinghouse.

Acknowledgments

The NIAMS gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the following individuals in the preparation and review of the original version of this booklet: Jill P. Buyon, M.D., Hospital for Joint Diseases, New York, New York; Patricia A. Fraser, M.D., Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; John H. Klippel, M.D., The Arthritis Foundation, Atlanta; Michael D. Lockshin, M.D., Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Disease, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, New York; Rosalind Ramsey-Goldman, M.D., Dr.P.H., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois; George Tsokos, M.D., Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland; and Elizabeth Gretz, Ph.D., Barbara Mittleman, M.D., Susana Serrate-Sztein, M.D., and Peter E. Lipsky, M.D., NIAMS, NIH. Special thanks also go to the many patients who reviewed this publication and provided valuable input. An earlier version of this booklet was written by Debbie Novak of Johnson, Bassin, and Shaw, Inc.

The mission of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health (NIH), is to support research into the causes, treatment, and prevention of arthritis and musculoskeletal and skin diseases; the training of basic and clinical scientists to carry out this research; and the dissemination of information on research progress in these diseases. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Information Clearinghouse is a public service sponsored by the NIAMS that provides health information and information sources. Additional information can be found on the NIAMS website at www.niams.nih.gov.

For Your Information

This publication may contain information about medications used to treat the health condition discussed here. When this publication was produced, we included the most up-to-date (accurate) information available. Occasionally, new information on medication is released.

For updates and for any questions about any medications you are taking, please contact: U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website: http://www.fda.gov Toll free: 888–INFO–FDA (888–463–6332) For updates and questions about statistics, please contact: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics Website: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs Toll free: 800–232–4636

This booklet is not copyrighted. Readers are encouraged to duplicate and distribute as many copies as needed.

RECOMMENDED READING

Make a free website with Yola